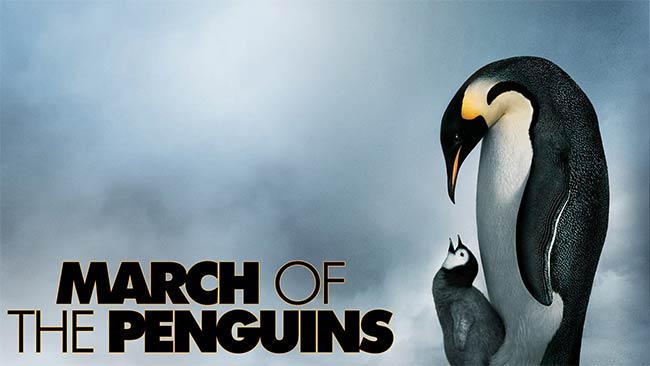

Image taken from the National Geographic film.

The Story of The Lone Penguin

Every year as the Antarctic summer ends and daylight fades into the long dark night of winter, colonies of Emperor Penguins set off from their feeding grounds near the sea to their breeding grounds inland.

Taking the cue from the change in the season, and from each other’s sense of urgency to be on the move, they form meandering lines and waddle off in procession for a journey of maybe sixty miles. Tens of thousands of them. These lines of waddling penguins converge at their ancestral breeding ground hidden away on the sea-ice in one of the remotest and most hostile places on earth.

Their first task is to hook up with last year’s mate, or to conduct an elaborate and noisy courtship ritual with the aim of attracting a new one. After everyone is paired up and has completed the necessary mating rituals, the female lays a single egg, holding it carefully on her webbed feet. This can take up to two months, from April through to June, during which time, far from the ocean, none of them has been able to feed. By now, it’s mid-winter, in perpetual darkness, with temperatures of minus sixty degrees and winds gusting to a hundred and twenty miles an hour. Within a few hours of laying it, the female shuffles her egg over to the male, carefully avoiding any contact with the ice. He nestles it onto his own feet and covers it with the feathery blubber of his tummy. If the egg rolls off, the chick will die. Many do. It’s a hazardous undertaking.

Now the females set off in line back to the ocean to feed and fatten, leaving the males in a massive huddle trying to gain some warmth as they incubate their eggs. To conserve energy as they endure blizzards and conditions which would freeze anything else to death, they sleep for twenty hours a day. Six weeks later, the eggs begin to hatch. And soon the females return to feed and nurture their chicks, and to relieve their mates who by now have fasted for nearly four months and lost half their body weight. Now the males set off in long lines, weakly waddling back towards the ocean in search of fish.

Meanwhile, the chicks grow, fed by regurgitation from their mums’ gullets. For some of the males, they’ve had enough. They stay at the ocean, leaving their spouse to handle junior. But others return yet again to the breeding grounds, carrying fresh food for the youngsters. By November, the chicks are huddling together themselves, spring is in the air and soon they can all start the long march back to the sea and their summer feeding grounds. But even now the adults face a dilemma. If they leave too early, the chicks may not yet be strong enough and will die en route. If they leave it too late, they themselves will not be able to feed again as their winter feathers moult and lose their waterproofing.

Now imagine for a moment, if a smarter than average penguin thought: “Hey, why do we do all this? Why don’t we just stay by the sea and save all this walking and exposure? Fewer of us would die, our chicks would grow faster and bigger, and we wouldn’t have all that hassle of hiking backwards and forwards in the gales and the freezing snow.”

He would die, because he would have no mate. His rebellious (but sensible) genes, would not be passed on. The lone penguin will not survive the winter.