First published in A Portrait of Kenya, a 2009 Government of Kenya promotional publication.

Think of wildlife and you think of Africa. Think of big game, the ‘Big Five’, the world’s greatest wildlife spectacles, and your mind turns to East Africa. But think of a classic wildlife safari across sun-kissed African savanna and of course you think of Kenya. Other countries may share Kenya’s astonishing wildlife diversity but for its photogenic nature and easy accessibility, Kenya surely takes the gold.

It is no exaggeration to suggest that the very existence of Kenya as a sovereign territory owes a great deal to the abundance and visibility of its wildlife. Early Arab and European explorers and traders gave what is now Kenya a wide berth on account of their fears of marauding bands of Masai warriors. Joseph Thomson broke this particular spell in 1884 when he discovered that a degree of humility and good neighbourliness paid dividends and avoided hostility. As a result, it became possible that the route from the Indian Ocean into the interior of East Africa could be reduced in both time and distance by using Mombasa instead of Zanzibar as a jumping off point, trekking directly up-country towards Lake Victoria instead of taking the more arduous and circuitous route through central Tanganyika and around the southern end of the lake.

A few years later came about the permanent route for both railway and road which continues to serve so well up to the present day. The construction of the railway from Mombasa to the shores of Lake Victoria in the final years of the nineteenth century gave European visitors the opportunity to see just what incredible wildlife spectacles existed in this part of the world. Instead of having to march for weeks on end with long caravans of porters, hunters, naturalists and other tourists could now watch big game from the comfort of their carriage.

Although big game hunting in all its guises – sport hunting, trophy hunting and the ivory trade – formed the early core of the fledgling safari business, this led in a short space of time to what has subsequently become the massive wildlife tourism industry which now forms one of the greatest contributing sectors to the Kenyan economy.

Cherry Kearton, one of the world’s first wildlife photographers, visited Kenya on safari in 1910. Here’s what he had to say about his first impressions. (From Photographing Wildlife around the World, by Cherry Kearton, Arrowsmith Books, London, 1913)

“I had, of course, heard a great deal about the railway and of the nature of the journey itself, but I was not prepared for the marvels I saw.

I spied a troop of ten giraffe, so close to the permanent way that I could have hit them. Evidently they had become quite accustomed to the trains. I was, perhaps, more excited than those giraffe were, but as the hours went by I grew accustomed to it, although I had never expected to see one tenth of the number of game. Literally, it was Nature’s Zoo. All the time the numbers seemed to increase, until you began to wonder how it was possible for so many to find pasturage. Zebra, wildebeeste, kongoni, Thomson’s gazelle, Grants, eland, ostrich, a lion and a rhino – we saw all these actually from our railway carriage. During the last forty miles, whilst we were crossing the great Kapiti and Athi plains, it was impossible for anyone possessed of ordinary eyesight to look out and not see game of some sort or another.”

Even today, visitors arriving at Jomo Kenyatta International Airport are just as likely to spot a troop of giraffe on the plains adjacent to the airfield, and the dry season migrations of plains game into Nairobi National Park can have just the same lasting impact as they did a hundred years ago.

Diversity of habitats

There are two secrets behind the wonder of Kenya’s wildlife – a marvellous climatic diversity leading to a plethora of different habitats, and a strong cultural legacy of custodianship from indigenous tribes such as the Masai. Kenya straddles the equator, which gives it two seasonal cycles each year as the sun passes back and forth between the tropics, trawling rain clouds behind it. The country’s ecological zones span the greatest possible range from beneath the ocean to the snowfields and glaciers at over 17,000′ on Mt Kenya. At least seven distinct habitats can be characterised, based on varying altitude, rainfall and climatic conditions.

The pelagic ocean habitat lies offshore, where the seasonal winds and currents flow alternately up and down the East African coast line. The steady ‘Kaskazi’ monsoon blows from the north east from November to March. This is the wind which in ancient times brought sailing dhows and settlers from the southern Arabian peninsula to form the characteristic East African coastal culture we now know as Swahili. But the currents bring too shoals of billfish – marlin, sailfish and swordfish – along with tuna, dorado and barracuda, sharks and whales. The deep sea fishing grounds off Watamu in the north and Shimoni in the south are considered by sport fishermen to be among the best in the world and many records have been taken here. Nowadays, a tag-and-release scheme ensures that this big game of the ocean remains numerous, while important research has revealed that these denizens of the deep undertake massive migratory journeys which encircle virtually the entire Indian Ocean from Kwa-Zulu Natal in the South all the way round via Arabia and India to Western Australia.

Along the shoreline itself, Kenya possess one of the finest stretches of coral reef in the world, forming in turn part of one of the world’s longest reefs which runs more or less uninterrupted for 4,000km from Somalia to Mozambique. Coral reefs are living ecosystems which accommodate an enormously diverse range of species. Snorkellers and divers can see lobsters, octopus, turtles, and a huge variety of colourful reef fish such as parrot fish, wrasse, angel fish, clown fish, box fish, and a host of others.

Much of Kenya, as indeed much of Africa itself, consists of the wide open spaces variously referred to as plains, steppe or savanna. This is the Africa of infinite cloudscapes, of distant horizons, baked by the midday sun but where you can watch stars rise and set at night. Savanna comes in a number of types depending on the amount of rainfall it receives on and on its soil type. This in turn affects the type of vegetation. Dry grass savannas are home to the vast herds of gazelle, antelope and zebra that are often called ‘plains game’. These species are grazers, able to exploit what to other creatures might be just straw or woody stems. But the abundance of these large mammals testifies to the sheer productivity of the savanna ecosystem which although often dry is able to turn the cellulose fibres of its grasses into protein to build muscle and bone. Typical mammals of the grass savannas include hartebeest, wildebeest, oryx and oribi. On the short-grass plains, pock-marked by termites mounds, Thomson’s gazelle, bat eared fox and nocturnal spring hares are the characteristics species. Thornbush savannas possess a dense, sometimes impenetrable, growth of prickly vegetation which deters some species while offering sanctuary to others. These areas are typically less used by humans and livestock and may provide shelter and nourishment to antelopes such as lesser kudu, gerenuk and dikdik.

Acacia savannas support a speckling of the tree that so characterises the habitat, the flat-topped umbrella tree or Acacia tortilis. In such areas, ‘tree islands’ may emerge as clusters of woody vegetation in a sea of grass. They may also grade into denser dry woodlands which typically form a transition zone between the open plains and other habitats. This is the preferred habitat of browsers such as impala, giraffe and elephant. The reedy or bushy vegetation where savannas merge into swampy areas near lakeshores and river banks is home to mammals such as waterbuck, reedbuck and buffalo.

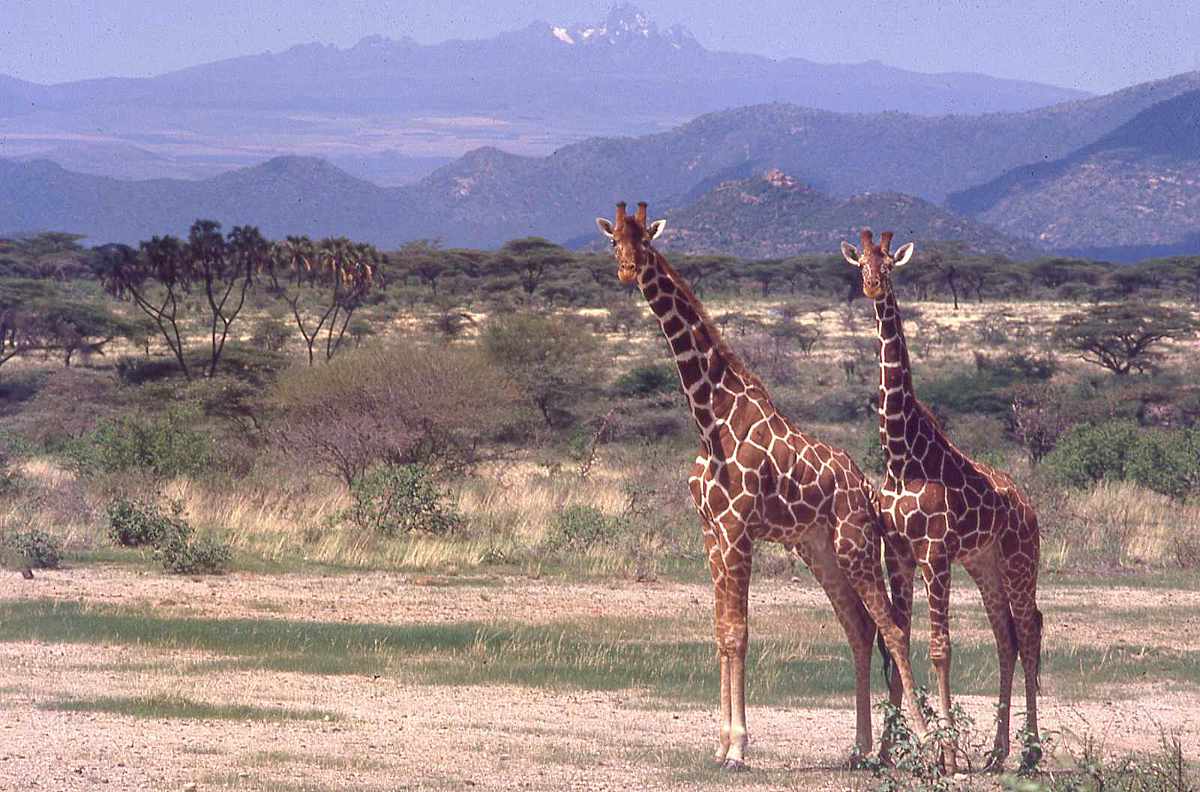

Semi-desert terrain exists across a huge swathe of northern and eastern Kenya covering almost half of the land area. This habitat consists of open sandy areas interspersed with varieties of thornbush and some grasses. Particularly where open water occurs, wildlife can be plentiful, from blossoming flowers after the rains, to clouds of butterflies, huge flocks of seed-eating birds and mammals such as dikdik, gerenuk and reticulated giraffe.

In Kenya, tropical forests or rain forests are confined to the moister zones in the west of the country and on the flanks of the higher mountain ranges such as the Aberdares, Mt Elgon and Mt Kenya. Much of the Kenyan highlands was formerly covered in forests of various kinds but this is the first habitat to fall to the influence of human settlement and relatively little remains. A great deal of what is left continues under threat. Great swathes of the Mau escarpment – the high lying land between Naivasha and Kericho – has been devastated by bulldozers, chainsaws and fire, contributing, it is supposed, to localised climate change and a greater frequency of drought. Moist forests, ecologists tell us, act as the lungs of a nation, breathing life into the atmosphere and soil. The long term effects of the loss of forest cover has yet to be fully felt. Meanwhile, much of the Kenyan rain forests continues to be accessible to visitors but although wildlife is often abundant it can be difficult to see. Elephant and small antelope called duiker are amongst the characteristic species of forests, and monkeys can often be seen swinging and clambering around the treetops. Species include black and white colobus and Sykes’ monkeys, though in the Kakamega forest, a remnant patch more typical of the great central African forest, a much greater range of arboreal monkey species can be found. Forests range in Kenya’s equatorial highlands to over 9,000′ in altitude at which level, the habitat gives way to moorlands of tussock grass and giant heathers. Here, in concentrated ultra violet light but with chillingly cold night time temperatures, strange overgrown species of plants grow – giant versions of groundsels and lobelias whose nectar is sipped by long tailed malachite sunbirds. Mammals too have adapted to this environment and it is not unusual to see jet black serval cats and leopards prowling in search of francolin, a kind of equatorial partridge.

Kenya’s landscape soars yet higher. Mt Kenya, the second highest in Africa, peaks at 17,058′. Above 15,000′ lies the snowline and perennial glaciers. Here, wildlife is less common, restricted to the occasional marauding raven and soaring vulture. But if these zones form the interlocking jigsaw puzzle that is Kenya’s ecology, other important pieces help fill in the gaps . . . lakes, rivers, islands, deltas, isolated craggy outcrops, mangrove swamps and wetlands. All these provide refuge to characteristic and sometimes unique wildlife species. And they provide unending excitement for both tourist and naturalist alike.

Although certain mammal species are characteristic to specific habitats, several occur in Kenya that have adapted to differing zones and evolved into separate races or closely related species. There are three types of giraffe, for example, the common or Masai race of the savanna woodlands, the three-horned Rothschild’s giraffe from western Kenya, and the more starkly marked and colourful reticulated giraffe which occurs in the semi-deserts in the north. There are two types of zebra, the common or Burchell’s zebra with the well-known black-and-white stripes and the more narrowly striped Grevy’s zebra which has tufty ears and lives in the northern semi-deserts. The Bohor reedbuck lives by lakeshores, the greyer and more slender mountain reedback can be found in hill country. The lesser kudu is common in thornbush scrub in parts of southern Masailand and in Meru National Park, while the more stately greater kudu with its spiralled horns occurs in Kenya only on the rocky outcrops of the Laikipia plateau and Samburu country. There are three varieties of hartebeest – the Coke’s or common occurring in the southern plains, Jackson’s in Laikipia, and the rare hirola or Hunter’s hartebeest confined to an enclave on the Tana River. The closely related topi occurs in the south west of Kenya and its close relative the tiang in the far north on the Sudan border. The geographical divide of the Great Rift Valley acts as a separator for some other species. The olive baboon lives to the east of the escarpment while the smaller yellow baboon thrives to the west. The ringed-rump or common waterbuck lives to the east while the patched-rump Defassa waterbuck occurs in the west. Oribi occur only to the west of the rift valley while another smaller antelope, the suni, occurs only to the east.

It’s not only mammals that can be seen in these diverse habitats. The variety of birdlife too is second to none, while a huge range of insect species and reptiles are also found here.

Seasonal cycles

The seasonal shifts of climate produce yet another fascinating feature of Kenya’s wildlife – the famous migrations. Many people have heard about the mass movements of wildebeest and other plans game including zebra and gazelle which take place each year between the vast Serengeti ecosystem and Kenya’s Masai Mara. But less well known are the spring and autumn migrations of palearctic bird species. Flocks of storks, eagles, ducks, waders and smaller perching birds fly literally thousands of kilometres to and from their summer nesting grounds in northern Europe. Within East Africa, other species undertake shorter flights to their seasonal haunts.

When the rains come in April, the fields turn green, the flowers bloom and the trees are full of the noise of birds building nests and attracting mates. For three months or so, this is the season of cool air and clear skies, fresh mornings and nippy nights. Plentiful water and grazing means that wildlife can roam free, spreading out over vast tracts of land throughout southern Kenya in particular. But as the drought bites towards September and October, diminishing supplies draw the herds back to the perennial pastures and waterholes protected by the parks and reserves.

For another three months, the plains fill with incoming game until the short rains come again in November. Then the half year cycle repeats itself again. Thus Kenya enjoys two seasonal cycles each year, with two green seasons full of colour and activity and two dry seasons when the parks fill with game.

Images of wildlife

Images of Kenya’s wildlife held in the mind or on photographic paper last for a lifetime and help retain the visitor’s sense of wonder – and also help explain why an African safari is at the top of the ‘must do’ list for so many people from the industrialised world . . .

. . . a giraffe silhouetted against the golden setting orb of the sun . . . a prowling dappled leopard in the fading light of dusk . . . a dancing ostrich with its ‘orphanage’ of young prancing along behind . . . a lyre-horned impala leaping effortlessly over a high fence . . . skeins of candy pink flamingos undulating across a lake . . .

The extraordinary variety is unending and truly astounding. Kenya’s register of wild animals includes horses (zebras), ungulates (buffalo, antelopes), cats (lions, leopards, cheetah), dogs (wild dogs, hyena), pigs (warthog, giant forest hog, bushpig), rodents (rats, porcupines, mice, squirrels), monkeys, bushbabies, aardvarks, rabbits and hares, hedgehogs . . .

The biggest mammal is the African elephant, actually holding the record as the largest land mammal in the world weighing in at up to six tonnes. The white rhino, although not strictly indigenous to Kenya, is next at 2.5 tonnes followed by the hippo at 1.5 tonnes. The black rhino is more lightly built than the white variety and weighs around a tonne. A mature bull buffalo can weigh about 750 kg.

The tallest animal in the world is the Masai giraffe which can grow to over five metres tall.

The biggest antelope is the massively built eland which can grow up to 500 kg. Great kudu, wildebeest, Oryx and sable can all clock in at around 230 kg.

At the other end of the scale, the smallest antelopes to be found in Kenya are the suni and dikdik which measure only 30 cm or so at the shoulder and weigh a mere 5 kg.

Amongst the antelopes, there is too a fascinating variety in the shape of their horns, with the males typically possessing the most impressive sets. The sable’s are massively back-swept scimitars, the oryx’s long straight spears, the kudu’s dramatic spirals, the duiker’s short sharp spikes.

Visitors’ fascination is most characteristically captured by the big cats, especially the lion, the cheetah and the elusive but surprisingly common leopard. The ‘Big Five’ was the term used to describe the top five trophies sought by hunters – lion, leopard, rhino, buffalo, and elephant. But modern day tourists are often just as excited at the antics of a host of smaller animals that can be seen around their camps and lodges. These include genets, mongooses, squirrels and hyraxes.

While beauty lies very much in the eye of the beholder, there is some consensus about the most attractive wildlife species. Many people’s favourite is the elegant and lovely spotted cheetah with its characteristic ‘teardrop’ facial markings but the leopard, more common but less often seen during daylight, also possesses a gorgeous shining coat marked with black rosettes. The delicate stripes of the bongo and male bushbuck are also highly attractive, in both species set against a glowing russet background. The Grevy’s zebra and the reticulated giraffe are particularly photogenic, especially amid the sometimes stark semi-desert terrain of their natural home.

These fantastic images no longer rest exclusively in the realms of the professional photographer. Any and every visitor to Kenya stands a good chance of achieving them, though a strong pinch of luck is an important ingredient on most game drives.

Also fixed in the memory and stimulating the senses are the sounds of the African bush which reverberate across the plains and echo amongst the trees . . . the splash and grunt of a hippo in the night . . . the haunting cry of a fish eagle . . . the boom of the colobus in the forest canopy . . . the ghostly shriek of the tree hyrax . . .

. . . in an eery silence, a herd of over 400 elephants marched across the rolling Tsavo plains as if they had a date with destiny . . . they did, little did we know it. During the 1980s in particular, poachers armed with automatic rifles laid waste to Kenya’s wildlife heritage as never before, decimating the herds. Parts of Tsavo National Park resembled a battlefield with scattered corpses and spent cartridges. A closely guarded group of white rhino in the heart of Meru National Park was wiped out under the noses of rangers. Zebra and antelopes were snared in thousands to supply a thriving trade in ‘bush meat’. These were dark days for Kenya’s wildlife and no less for the parks and reserves themselves as a land-hungry population erected more and more settlements and planted more and more crops.